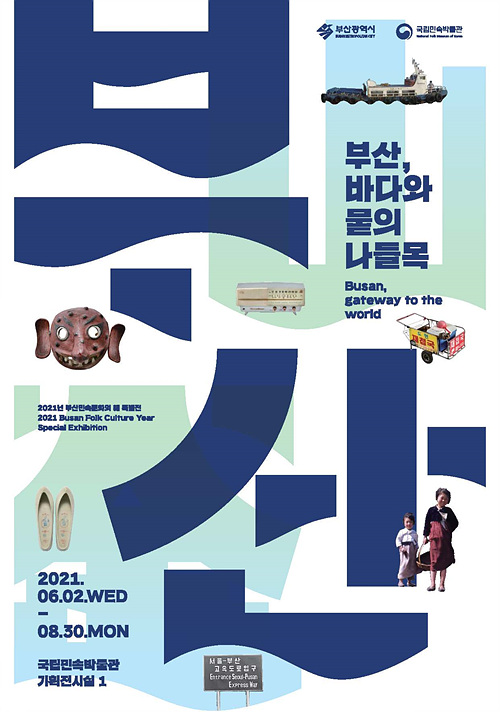

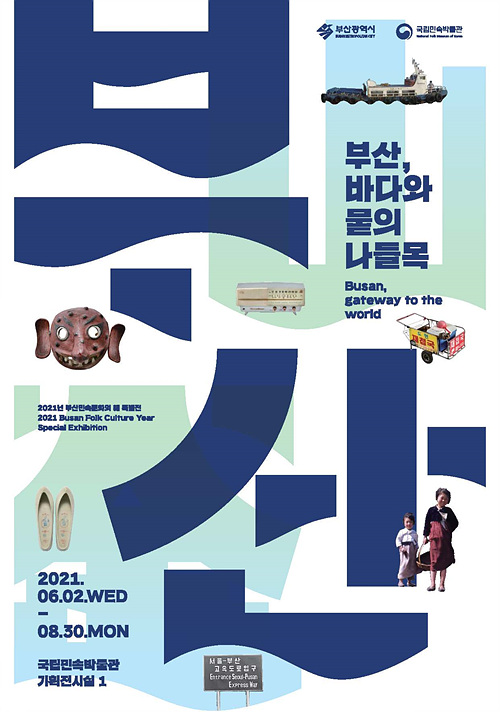

Overview

Busan Metropolitan City and the National Folk Museum of Korea present the special exhibition "Busan, Gateway to the World", celebrating the "2021 Year of Busan Folk Culture". As part of the "Local Folk Culture Year", this exhibition aims to discover local folk culture using existing academic findings and research conducted by Busan Metropolitan City and the National Folk Museum of Korea from 2019 to 2020.

Although today’s Busan is often associated with the sea, the area was centered around the inland district of Dongnae until the Joseon Dynasty (1392 – 1910). Later, Busan developed with the sea and has become Korea’s representative maritime city. The country’s first modern open port, the city is an intersection of people, goods, and cultures. It became the pillar of the nation while serving as a refugee capital during the Korean War, and as the first directly governed city of Korea, it has acted as a foothold for export trade. This exhibition looks back on the life and people of Busan, a city that is an invaluable part of both Korea and its history.

The exhibition consists of two parts: "Part 1. Busan, the Intersection of People, Goods, and Cultures", which details the history of Busan as a major port, and "Part 2. Busan, the Coexistence of Farming and Maritime Cultures", which introduces the lives and stories of the Busan people.

We hope that through this exhibit, visitors can learn about Busan as a place where diverse cultures coexist and relate to the lives of the people living amongst those cultures.

Part1. Busan, the Intersection of People, Goods, and Cultures

Busan, located at the southeastern point of the Korean Peninsula, has served as a maritime gateway where people and goods come and go. During the Joseon Dynasty, it was the center of exchange with Japan, where trade was conducted as Korean envoys to Japan (tongsinsa) came and went and Japanese envoys were greeted at Choryang Waegwan, a Japanese settlement. Busan would become a passageway for new cultures as the country’s first modern open port, but during the Japanese occupation period, it was used for exploitation and forced mobilization.

During the Korean War, refugees, military supplies, and foreign aid rushed in, and as people, goods, and cultures merged, Busan became the city it is today. The opening of Gyeongbu Highway enabled local industry to spread nationwide and brought about even greater development, and with the construction of container docks, the city became a major outpost for export trade. As such, Busan carried out exchange with the outside world, facilitating the intersection of people, goods, and cultures—and, at times, withstanding enemy invasion. To this day, this history is ingrained in the minds of Busan people, as many identify as people who fight against injustice and are open to new cultures.

Military Hub and Cultural Gateway

Being close to Japan, Busan has frequently been threatened by Japanese invasion, including the Imjin Waeran (Japanese Invasion of Korea in 1592). In 1397 (the sixth year of King Taejo’s reign), an outpost was constructed in Busanpo Port, and in 1592 (the 25th year of King Seonjo’s reign), when the Imjin Waeran broke out, the Gyeongsang Jwasuyeong (Left Naval District of Gyeongsang-do) moved in current Suyeong area to maintain border security.

Busan has also been where Korean envoys to Japan frequently passed between the countries, and a place that saw Japanese settlement in the form of diplomatic and commercial businesses that welcomed Japanese envoys and facilitated exchange. Even though Busan was far from the capital Hanyang (now Seoul), it was both an important military hub that guarded against Japanese invasion and a diplomatic and cultural gateway to Japan.

Base of Exploitation with a Surge of New Cultures

When the Treaty of Ganghwa was signed in 1876, Busan became the first modern open port in Korea under pressure from world powers, and Choryang Waegwan was transformed into a settlement and concession (jeongwan georyuji) where Japanese had autonomy. In 1883, government offices such as Gamniseo (superintendent office) and Haegwan (maritime customs building) were established near the Port of Busan, and as Westerners made frequent visits to the city, it became a passageway for Western culture. With the Bukbin (current Busan North Port) Reclamation Project in 1902, which reclaimed Busan’s waters, and the construction of facilities such as Japanese settlements and concessions, docks, and Busan Station, which enabled the transportation of exploited goods, Busan began to resemble a modern city despite the cloud of invasion still hanging over it.

Refugee Capital

With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Busan became the country’s temporary capital city and a destination for refugees displaced by the war who flooded into the city. The refugees built shacks along the coast and mountain ridges, which created a unique cityscape that can be described by the words sandongne (hillside village) and sanbokdoro (the roads in the middle of mountain). Although times were tough, a new culture was budding in Busan. Korea’s finest artists made paintings on pottery and refugees from North Korea created milmyeon (wheat noodles), a variation of the naengmyeon (cold noodles) they had eaten back home. Thus, Busan came to possess acceptance and diversity as people from all over the country blended together within its boundaries.

Foothold of Export Trade

As Busan’s population increased with the outbreak of the Korean War, goods such as daily necessities became concentrated in Busan. Smuggled products from abroad gathered in Busan’s Gukje Market and spread out to different parts of the country. As foreign aid and raw materials came in via the Port of Busan and factories were constructed, industry developed in areas such as lumber and rubber. Since the 1960s, the government has enforced an export-oriented economic development policy and as part of this, Gyeongbu Highway opened in 1970, completely transforming transportation in Korea by enabling a one-day trip between Busan and Seoul. As the Port of Busan was restructured as a container port, Busan became the foothold of export trade in Korea.

Part 2. Busan, the Coexistence of Farming and Maritime Cultures

Until the Joseon Dynasty, people in Busan primarily made a living through agriculture. Busan’s farming culture has survived to this day through a number of folk practices including yaryu, a mask dance drama that began in village festivals, and nongcheong nori, which originated from the labor songs of farming communities.

The sea has also been the foundation of life for people in Busan for a long time. The life of local fishing communities has been maintained in cultural properties such as eobang nori (fishing village festival) and byeolsingut (village ritual). It was not only men who engaged with the sea, but women as well; the ocean was the workplace for the Busan haenyeo (women divers) and the kkangkkangi ajimae (female workers who remove rust from ships) of Yeongdo Island, located between the city’s harbors and the open sea. Jaecheop Village, named for its abundance of marsh clams (jaecheop), sprung up where the Nakdonggang River meets the sea and brought about the jaechitguk ajimae (female vendors of marsh clam soup), who still are the first to greet Busan every morning. Additionally, the coastal seafood market still remains vital for jagalchi ajimae (female merchants at Jagalchi Market) to support their families. As such, Busan is a diverse place where farming and maritime cultures coexist. This coexistence is the root that created today’s Busan and will be the foundation of the city’s future.

Maintaining Farming Rituals and Culture through Yaryu

Yaryu, meaning "mask dance drama" and also called deulnoreum, is a form of entertainment in which people wear masks and play in a large field. This mask play originates from the region east of the Nakdonggang River. Fields (deul), of course, are where agriculture takes place, and the existence of yaryu demonstrates that Busan centered on farming until the Joseon Dynasty.

Suyeong Nongcheong, Folk Entertainment in a Farming Community

In order to work more effectively, farmers in the Suyeong region organized farming communities called nongcheong, which are similar to dure (a type of collective labor operation within small farming communities). The Suyeong nongcheong, which retained this original form, lasted from the Joseon period to the 1960s. Suyeong’s farming culture, centered around nongcheong, was excavated as an artifact of folk entertainment and designated as Busan Metropolitan City Intangible Cultural Property No. 2 in 1972.

Jwasuyeong Eobangnori, Folk Entertainment in a Fishing Community

Suyeong also possessed an eobang, a fishing community of naval forces and fishermen. In eobang, naval forces provided labor and fishermen distributed part of their catches in ordinary times; in wartime, fishermen would serve in the navy in their fishing boats. In Suyeong, fishermen who caught anchovies using hurit geumul (seine) formed an eobang, and this tradition has been passed down in the form of a folk entertainment practice called the Jwasuyeong Eobangnori.

Donghaean Byeolsingut, Village Ritual for Safety and Abundance

In Busan’s fishing villages, people have long held large-scale shamanic rituals (gut) called byeolsingut by inviting a shaman to the village to pray for the community’s wellbeing, and large catches of fish and a safe voyage for the fishermen. In some fishing villages, villagers still collect money to perform this ritual.

Busan jimae Living with the Sea

In Busan, there are haenyeo who harvest seafood while wearing just rubber diving suits. Downstream Nakdonggang River, in Jaecheop Village, jaechitguk ajimae sell the village’s signature marsh clam soup every morning. Kkangkkangi ajimae remove rust from ships using hammers, their nickname derived from the "kkangkkang" sound of hammers against the surface of the ships. At Jagalchi Market, jagalchi ajimae have become the symbol of the seafood market. These women are living proof of Busan’s history. They have lived fiercely to support their families while surviving the Korean War and industrialization, and still remain an integral part of Busan’s present.